A natural question of humankind is whether life exists elsewhere. Scientists are currently looking in our solar system and beyond for planets, moons, and other objects that have the potential to harbor the only thing we know to sustain life—liquid water. Also key to life, however, is the ready availability of oxygen on and around a celestial object’s surface.

One body that scientists looking for habitable worlds are focusing on is Jupiter’s icy moon Europa, which lies 390 million miles from Earth. Evidence shows Europa holds a massive subsurface ocean beneath its icy shell, a counterpart to the life-harboring water we have here on Earth. In 1995, NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope identified the presence of oxygen in Europa’s atmosphere. These molecules could potentially be oxygenating its subsurface ocean, much like what occurs on our own planet—but estimates of how much oxygen is present have varied.

Now, a new Nature Astronomy study, coauthored by LASP researcher Fran Bagenal, has used data from NASA’s Juno mission to dive deep into Europa’s atmosphere and take a closer look at its chemical make-up. Researchers found evidence that there is a much narrower range of molecular oxygen in the moon’s atmosphere than models had previously estimated.

The new findings are challenging previous estimates of the habitability of the ice-covered moon. “Now, I’m not a biologist,” Bagenal says, “but my understanding is that life on Earth may have started in the oceans; and you have to bring in oxygen.”

Bagenal suggests that the decreased oxygen levels aren’t necessarily negative, however. Instead, they serve to narrow down the margins of error. “I think what’s important is it quantifies [the oxygen] and gives you a sense of a more realistic number,” Bagenal explains.

The measurements were taken from the Jovian Auroral Distributions Experiment (JADE) instrument onboard the Juno space probe, which was launched in 2011 and arrived at Jupiter in 2016. JADE’s primary function is to detect and measure ions and electrons around the spacecraft. During a single close pass of Europa on September 29, 2022, however, JADE effectively captured information on many chemicals for the first time, including hydrogen and oxygen, which are formed when charged particles in space break apart the ice molecules present on Europa’s surface.

On Europa, some of this oxygen found in the atmosphere could be getting absorbed by the seemingly porous ice. So, the question now becomes whether the oxygen molecules found during the flyby are penetrating the thick ice and mixing with the oceans under the surface. It’s too early to say this oxygen is evidence of habitability, Bagenal says, but rather it supports the possibility of generating the right chemicals to make life.

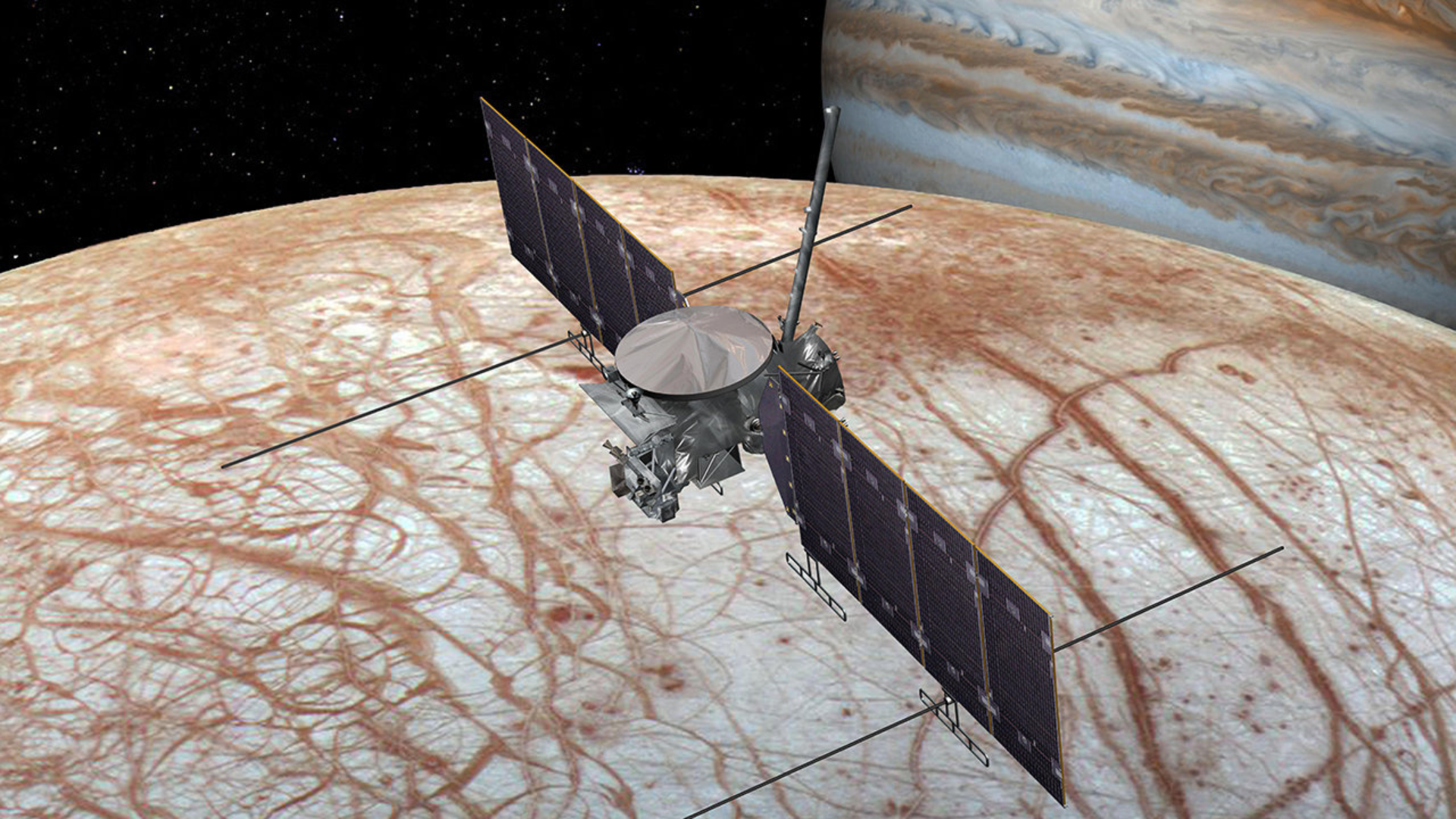

Unfortunately, Juno will not be passing by Europa again, and the next opportunity to confirm the findings will now shift to NASA’s Europa Clipper mission, which is expected to launch this October and arrive at Europa in 2031.

Clipper will have instruments on board ready to analyze the surface composition, ice thickness, and the plasma environment of Europa. Among these instrument’s will be LASP’s Surface Dust Analyzer (SUDA) dedicated to measuring dust grains and providing insights into their composition.

Many questions raised by this study will hopefully be answered by SUDA, including whether the surface layers themselves are oxidized. Bagenal says it’s possible that data gathered by Clipper could dismiss the whole idea of subsurface oxygen and toss it out the window entirely. “But that’s okay,” she says. “That’s the way we do science, right?”

The challenge lies in the decade-long wait for more answers.

By Emma Opper, Science Writer

Founded a decade before NASA, the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics at the University of Colorado Boulder is on a mission to transform human understanding of the cosmos by pioneering new technologies and approaches to space science. LASP is the only academic research institute in the world to have sent instruments to every planet in our solar system. LASP began celebrating its 75th anniversary in April 2023.