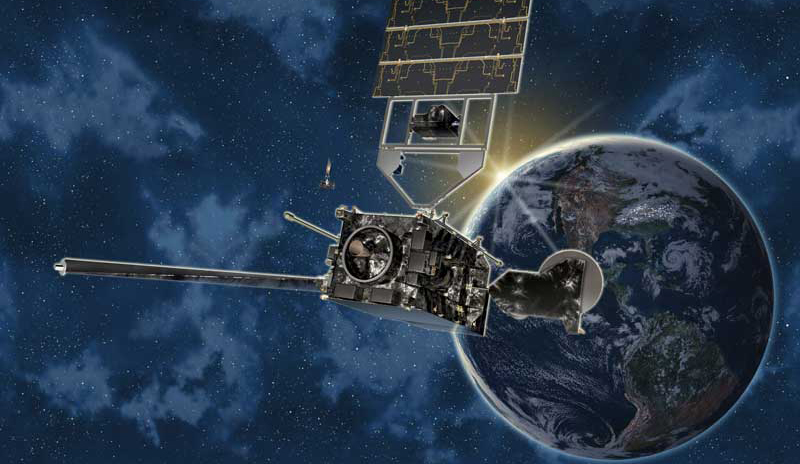

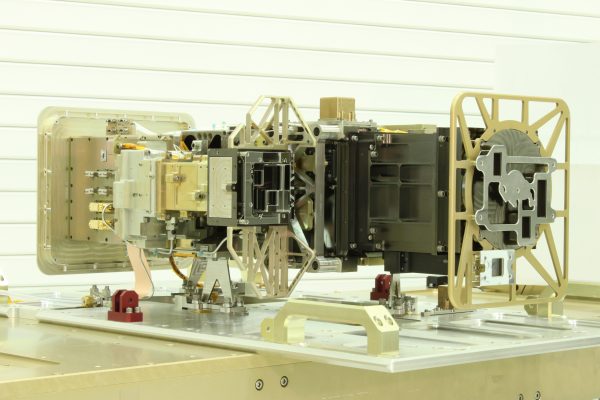

Built at LASP, the instrument suite known as the Extreme Ultraviolet and X-ray Irradiance Sensors (EXIS) is the second of four identical packages that will fly on NOAA’s next-generation Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellites-R Series (GOES-R). As part of the NOAA weather forecasting satellite series, EXIS measures energy output from the Sun that can affect satellite operations, telecommunications, GPS navigation, and power grids on Earth.

GOES-S, the second satellite in the series, launched at the first available opportunity at 3:02 p.m. MST, hurtling from Cape Canaveral, Florida, towards geostationary orbit—22,300 miles above the Earth—atop a United Launch Alliance Atlas V rocket. Lockheed Martin Space Systems Co. in Littleton, Colorado built the GOES-S satellite.

“GOES-S had a picture-perfect launch and we look forward to a successful mission,” said LASP Senior Research Scientist Frank Eparvier, principal investigator on the EXIS project. “These extremely sensitive instruments will help scientists better understand solar events and help to mitigate the effects of space weather on Earth.”

EXIS consists of two instruments designed and built at LASP, including XRS, an X-ray sensor that can determine the strength of solar flares and provide rapid alerts to scientists, said Eparvier. Large solar flares, equivalent to the explosion of millions of atomic bombs, can trigger “proton events” that send charged atomic particles flying off the Sun and into Earth’s atmosphere in just minutes. They can damage satellites, trigger radio blackouts and even threaten the health of astronauts by penetrating spacecraft shielding, he said.

“The XRS gives the first alert that a solar flare is occurring, providing NOAA with details on its timing, magnitude and direction within seconds,” said Eparvier.

The second EXIS instrument, EUVS, will monitor solar output in the extreme ultraviolet portion of the electromagnetic spectrum, which is completely absorbed by Earth’s upper atmosphere, said Eparvier. When the extreme UV light wavelengths penetrate the upper atmosphere during active periods on the Sun, they can break apart, ionize and change the properties of the atmosphere through which satellites fly and radio waves propagate.

Fluctuations in extreme UV wavelengths from the Sun ionize the upper atmosphere and interfere with communication technologies like cell phones and GPS signals, said Eparvier. In addition, such fluctuations can create satellite drag, causing spacecraft to slowly fall out of orbit and burn up months or years before such events are anticipated.

“Modern technology has made us vulnerable to extreme variations in space weather that can have significant effects on Earth communications,” Eparvier said. “Extreme solar activity can cause problems for power companies all around the world, for example, in part because they all are interconnected.”

NOAA’s GOES satellites are a series of weather satellites that help scientists make timely and accurate weather forecasts. GOES-R, which launched in November 2016, is now operational as GOES-16 and focused on the eastern part of the Americas; GOES-S will become GOES-17 in about two weeks and will aid in forecasting weather for the western U.S., Alaska, and Hawaii.

Satellites in geostationary orbit complete one revolution in the same amount of time it takes for the Earth to rotate once on its polar axis, allowing them to “stare” at a specific location on the Earth, said Eparvier.

More than 100 LASP personnel, ranging from scientists and engineers to technicians, programmers, and students have worked on the EXIS program since 2006. LASP will support EXIS on the four GOES satellite missions through spacecraft integration, testing, launch and commissioning, said Eparvier.

Each instrument package, roughly the size of a large microwave oven and weighing 66 pounds, is three times heavier than normal due to extra shielding that protects them from high-energy particle penetration. LASP engineer Mike Anfinson is the EXIS project manager.

[addthis]