Fran Bagenal, a senior research scientist at the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics (LASP) at the University of Colorado Boulder and professor emeritus of the university’s Astrophysical and Planetary Sciences Department, has been inducted into the U.S. National Academy of Sciences (NAS).

The academy, which is widely regarded as the country’s most prestigious honorary scientific society, recognized Bagenal as “a leading expert on the properties of plasmas that pervade the magnetospheres of the outer planets”. She was one of 120 scientists elected to the national academy this spring, and one of 59 women—the most ever elected in a single year.

Since earning her Ph.D. from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1981, Bagenal has focused on the dynamic environs of planets dominated by their magnetic fields. She’s served on the science teams of the Voyager and Galileo missions and is currently a Co-Investigator for NASA’s New Horizons mission, which flew past Pluto in 2015, and for NASA’s Juno mission, which entered into orbit over the poles of Jupiter in 2016.

Being part of the national academy’s record-setting class is a point of pride for Bagenal, who serves as a national advocate for increasing inclusion, diversity, equity, and accessibility in STEM disciplines. She is currently co-chairing a NAS committee focused on increasing diversity and inclusion in the leadership of competed space missions, and she and other committee members will present their key findings during a public webinar this Wednesday.

We recently caught up with Bagenal to hear what inspired her career, what membership in the academy means to her, and the pathways the NAS committee recommends to break down barriers for all women and minorities in science and engineering.

LASP: What does your election to the National Academy of Science mean to you personally?

FB: Obviously, it is a great honor. Moreover, it’s an opportunity to pay back to the scientific community that has supported me throughout my career, through service on NAS and other committees.

LASP: What was the induction ceremony like?

FB: To be honest, it was pretty intimidating! All I had to do was to walk onto the stage and sign a book that’s 150 years old and has been signed by every academy member. But with bright lights, cameras, and a big audience full of famous people, it was scary!

LASP: Who inspired you to take this career path?

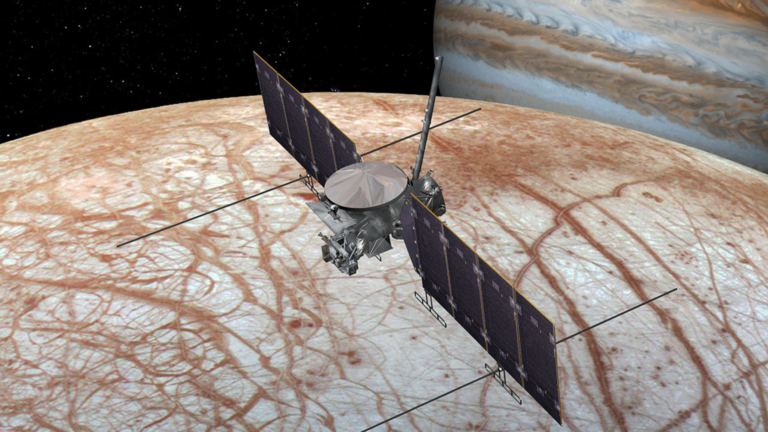

FB: As a kid, I watched lots of TV shows featuring Carl Sagan, who was very motivating. But from graduate school onwards, I particularly credit Margy Kivelson—a professor at UCLA—who inspired and encouraged me. She led the magnetometer team on the Galileo mission and is now running the magnetometer team for the upcoming Europa Clipper mission. She has a reputation as a pretty intimidating scientist who asks penetrating questions. But we have become good friends and enjoy long, deep conversations on a myriad of topics. She even attended the ceremony to support me!

LASP: What obstacles did you encounter in your career, and how did you overcome them?

FB: I admit that I suffered the classic “imposter syndrome” as a young scientist. But I got over it when I became a tenured professor here at CU. Otherwise, it’s been the usual challenge of prioritizing too many things to do—such as when to turn down service requests, how to focus on long-term research projects, and, ultimately, when to say yes and, how to say no.

LASP: How much time did chairing this committee take, and what challenges did you encounter?

FB: Over the past 20 months, this NAS committee has taken about half my time, particularly recently, as we’ve rolled out the report. But it’s important to understand why the leadership of competed space missions is so white and male. A particularly interesting challenge was for the committee’s mix of physical scientists and social scientists to talk to each other in language the others could understand.

LASP: What actions does the committee recommend NASA take to increase diversity and inclusion in mission leadership?

FB: While there are some actions that NASA could take immediately to make the competitions more transparent and fair—to level the playing field—the long-term problems stretch the full career pathway, from high-school education to professional research scientist. In fact, the “pinch-point” where the diversity in STEM education plummets is the first semester or so of physics and math at the college level. This is something the physics education research community here at CU has been pointing out and tackling for years.

Meanwhile, here at LASP, we hope to enhance the diversity of space sciences by working with Minority Serving Institutions to bridge between high schools and/or community colleges and CU by focusing on research experiences for undergraduates and incoming graduate students. Down the road, LASP also aims to leverage our 70+ years of experience of student-built and student-operated space missions to collaborate with Historically Black Colleges and Universities to help build their capacity for involving students in space missions.

LASP: You’ve already accomplished so much in your career! What do you plan to do next?

FB: The Juno mission has made 41 orbits of Jupiter, and we’re planning on another 35 over the next 4 years. These will be particularly exciting as the spacecraft will be passing through the region between the moons Europa and Io. There will be lots of fun science coming up!