The MAVEN spacecraft completed its commissioning activities on November 16 and has formally begun its one-year primary science mission. The start of science is actually a “soft start”, in that the instruments started making science measurements beginning almost as soon as we were in orbit, and some instrument calibration activities will be continuing throughout the mission.

Spacecraft commissioning, in what the MAVEN team called its “transition phase”, included adjusting the orbit to get into its science orbit, deploying the booms that hold a number of the instruments away from the spacecraft, ejecting the Neutral Gas and Ion Mass Spectrometer (NGIMS) instrument cover, turning on and checking out each of the science instruments, and carrying out calibration activities for both the spacecraft and the instruments. This period also included the close approach of Comet Siding Spring, which whizzed by Mars at a distance of only ~135,000 km on October 19.

During this transition phase, we were able to get some early science observations. We made observations from MAVEN’s initial 35-hour capture orbit immediately after the large Mars Orbit Insertion maneuver on Sept. 21. From this capture orbit, which took the spacecraft to much higher altitudes than our science-mapping orbit will, we used the Imaging Ultraviolet Spectrograph (IUVS) instrument to observe the extended clouds of hydrogen, carbon, and oxygen surrounding the planet. These “coronae” extend out to more than ten planetary radii, and this orbit allowed us to make measurements of the clouds’ spatial extent to higher altitudes than we can during the primary mission. We also took time off from commissioning to observe the comet and to take before and after observations of the Mars atmosphere to look for changes. IUVS and NGIMS observations both revealed a tremendous quantity of metal ions that came from cometary dust that entered the atmosphere. Their presence was unexpected, in that the nominal models of the paths taken by dust grains, calculated prior to the comet passage, indicated that no dust would make it all the way to Mars. We’re certainly glad that we took precautions to protect us from dust during the encounter!

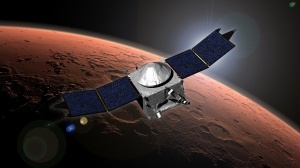

During science mapping, the spacecraft will carry out regular observations of the Martian upper atmosphere, ionosphere, and solar-wind interactions. MAVEN will observe from an elliptical orbit that gets as low as about 150 km above the surface and as high as 6000 km. The nine science instruments will observe the energy from the Sun that hits Mars, the response of the upper atmosphere and ionosphere, and the way that the interactions lead to loss of gas from the top of the atmosphere to space. Our goal is to understand the processes by which escape to space occurs, and to learn enough to be able to extrapolate backwards in time and determine the total amount of gas lost to space over time. This will help us understand why the Martian climate changed over time, from an early warmer and wetter environment to the cold, dry planet we see today.

From the observations made both during the cruise to Mars and during the transition phase, we know that our instruments are working well. The spacecraft also is operating smoothly, with very few “hiccups” so far. The science team is ready to go! Of course, standing behind the science team are literally hundreds of engineers who designed, built, tested, and integrated together the spacecraft and the science instruments, and who operate the spacecraft daily (and, when called upon, even in the middle of the night). The MAVEN team consists of researchers at the University of Colorado, NASA’s Goddard Spaceflight Center, University of California at Berkeley, Lockheed Martin, and NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, as well as colleagues at numerous other institutions who participated in developing the flight hardware and in doing the science analysis. Space exploration is a “team sport,” and the success of the whole team allows us to do our science.

With the formal start of our science mission, we’re on track to be able to carry out our full mission as planned, and the science team is looking forward to an incredibly exciting year!

[addthis]